The statement of cash flows using the indirect method has been discussed in most introductory accounting courses. Since the statement of cash flows can be challenging, a review of the basic concepts is presented below.

The purpose of the statement of cash flows is to provide a means “to assess the enterprise’s capacity to generate cash and cash equivalents, and to enable users to compare cash flows of different entities” (CPA Canada, 2016, Accounting, Part II, Section 1540.01 and IAS 7.4). This statement is an integral part of the financial statements for three reasons. First, this statement helps readers to understand where these cash flows in (out) originated from during the current year. This helps management, shareholders, and creditors to assess a company’s liquidity, solvency, and financial flexibility. Second, these historic cash flows in (out) can be used to predict future company performance. Third, the statement of cash flows can shed light on a company’s quality of earnings and if there may be a disconnect between reported earnings and net cash flows from operating activities, as explained earlier.

Two methods are used to prepare a statement of cash flows, namely the indirect method and the direct method. The indirect method was discussed in previous accounting courses and will be reviewed again in this chapter. The direct method introduced in this chapter may be new for many students. Both methods organize the reported cash flows into three activities: operating, investing, and financing. As discussed next, the difference between the two methods occurs only in the first section for operating activities.

The indirect method reports cash flows from operating activities into categories such as:

The direct method reports cash flows from operating activities into categories based on the nature of the cash flows, such as:

The statement of cash flows above for Wellbourn Services Ltd. is an example of a statement using the direct method. Note that the operating section line items using the direct method are based on the nature of the cash flows, whereas the indirect method line items are based on their connections with the income statement and working capital accounts.

There are some similarities between the two methods. For instance, the net cash flows from operating activities is the same for both methods, and the investing and financing activities are identical for both methods as well.

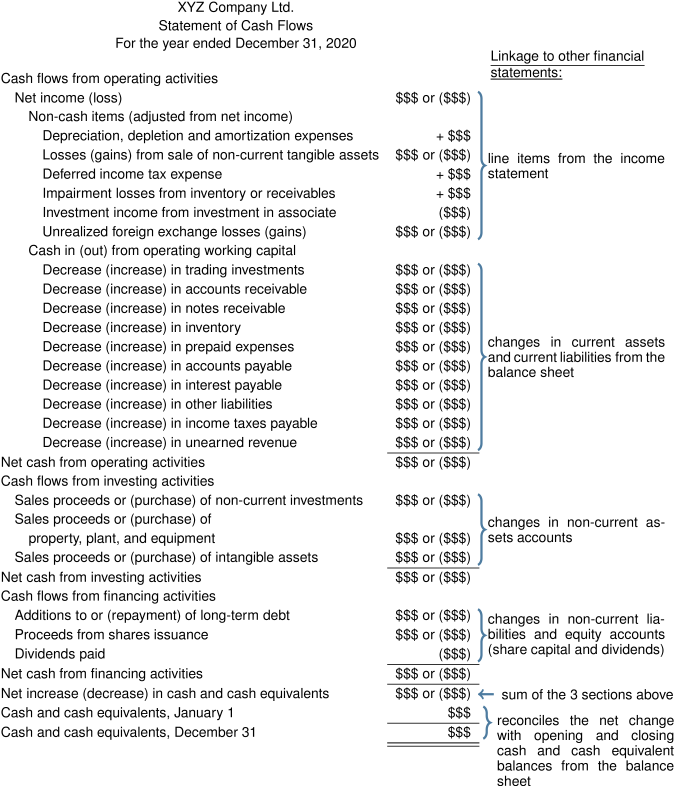

Below is an example of the format using the indirect method. Note the connections to the other financial statements.

There are differences in some of the reporting items between IFRS and ASPE. For example, ASPE has mandatory disclosures as follows:

For IFRS, there are policy choices that, once made, should be applied consistently:

For simplicity, this chapter will use the following norms for both IFRS and ASPE:

As illustrated above, when using the indirect method, the sum of the non-cash adjustments to net income and changes to non-cash working capital accounts result in the total cash flows in (out) from operating activities. The other two activities for investing and financing follow. Any non-cash transactions occurring in the investing or financing sections are not reported in a statement of cash flows. Instead, they are disclosed separately in the notes to the financial statements. Examples of non-cash transactions would be an exchange of property, plant, or equipment for common shares, or the conversion of convertible bonds payable to common shares and stock dividends. If the transaction is a mix of cash and non-cash, the cash-related portion of the transaction is reported in the statement of cash flows with a note in financial statements detailing the non-cash and cash elements. The final section of the statement reconciles the net change in cash flows of the three activities, with the opening and closing cash and cash equivalents balances taken from the balance sheet.

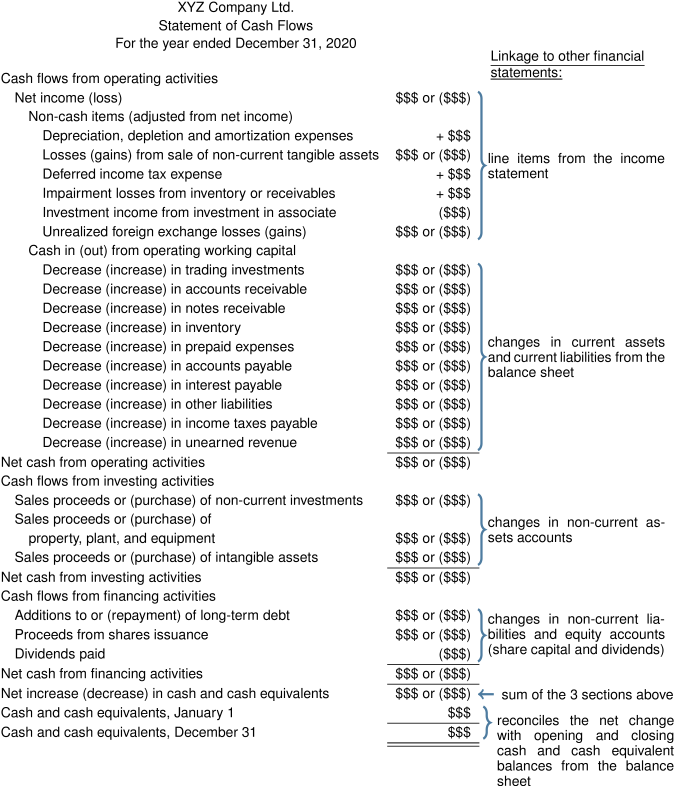

Presented below is the balance sheet and income statement for Watson Ltd.

Common (authorized, 400,000 shares; issued and outstanding (O/S) 250,000 shares for 2020);(2019: 200,000 shares issued and O/S)

| Watson Ltd. Income Statement As at December 31, 2020 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Sales | $3,500,000 | |

| Cost of goods sold | 2,100,000 | |

| Gross profit | 1,400,000 | |

| Operating expenses | ||

| Salaries and benefits expense | 800,000 | |

| Depreciation expense | 43,000 | |

| Travel and entertainment expense | 134,000 | |

| Advertising expense | 35,000 | |

| Freight-out expenses | 50,000 | |

| Supplies and postage expense | 12,000 | |

| Telephone and internet expense | 125,000 | |

| Legal and professional expenses | 48,000 | |

| Insurance expense | 50,000 | |

| 1,297,000 | ||

| Income from operations | 103,000 | |

| Other revenue and expenses | ||

| Dividend income | 3,000 | |

| Interest income from investments | 2,000 | |

| Gain from sale of building | 5,000 | |

| Interest expense | (3,000) | |

| 7,000 | ||

| Income from continuing operations before income tax | 110,000 | |

| Income tax expense | 33,000 | |

| Net income | 77,000 | |

The statement of cash flows is the most complex statement to prepare. This is because preparation of the entries requires analysis of multiple accounts. Moreover, the transactions resulting in cash inflows are to be differentiated from the transactions resulting in cash outflows for each account. Preparing a statement of cash flows is made much easier if specific sequential steps are followed. Below is a summary of those steps.

Here is a summary of the steps above, labelled with a key word or phrase for you to remember:

Applying the Steps:

Step 1. Headings:

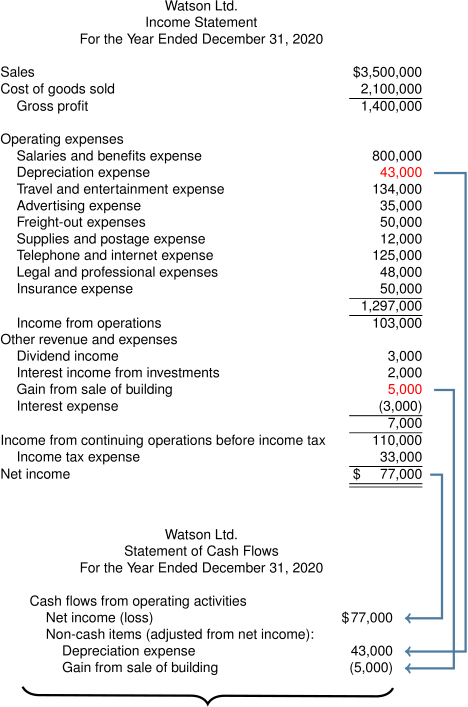

Step 2. Record net income/(loss):

As illustrated in step 3 below.

Step 3. Adjustments:

Enter the amount of the net income/(loss) as the first amount in the operating activities section. Next, review the income statement and select all the non-cash items. Look for items such as depreciation, depletion, amortization, and gains or losses (such as with the sale or disposal of assets). In this case, there are two non-cash items to adjust from net income. Record them as adjustments to net income in the statement of cash flows.

Step 4. Current assets and liabilities:

Calculate and record the change between the opening and closing balances for each non-cash working capital account as shown below (with the exception of the current portion of long-term notes payable, which is netted with its respective long-term notes payable account) as shown below:

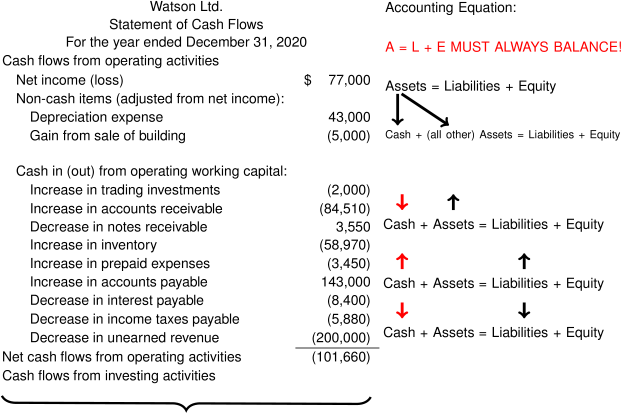

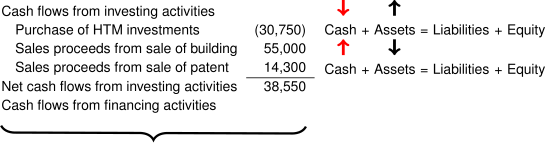

Cash inflows to the company are reported as positive numbers while cash outflows are reported as negative numbers using brackets. How does one determine if the amount is a positive or a negative number? A simple tool is to use the accounting equation to determine whether cash is increasing as a positive number or decreasing as a negative number. Recall the accounting equation:

Assets = Liabilities + Equity

This must always remain in balance. This equation can be applied when analyzing the various accounts to record the changes. For example, accounts receivable has increased from $165,000 to $249,510 for a total increase of $84,510. Using the accounting equation, this can be expressed as:

A = L + E

Expanding the equation a bit:

Cash + accounts receivable + all other assets = Liabilities + Equity

If accounts receivable INCREASES by $84,510, then this can be expressed as a black up-arrow above the account in the equation:

![]()

Holding everything in the equation constant, except for cash, if accounts receivable INCREASES, then the effect on the cash account must have a corresponding DECREASE in order to keep the equation balanced:

![]()

If cash DECREASES, then it is a cash outflow and the number must be negative with brackets as shown in the statement above.

Conversely, when analyzing liability or equity accounts, the same technique can be used. For example, an increase in account payable (liability) of $143,000 will affect the equation as follows:

![]()

Again, holding everything else constant except for cash, if accounts payable INCREASES as shown by the black up-arrow above, then cash must also INCREASE by a corresponding amount in order to keep the equation in balance.

![]()

If cash INCREASES, then it is a cash inflow and the number will be positive with no brackets as shown in the statement above.

Step 5. Non-current asset changes:

The next section to complete is the investing activities section. The analysis of all of the non-current assets accounts must also take into account whether there have been any current year purchases, disposals, or adjustments as part of the analysis. The use of T-accounts for this type of analysis provides a useful visual tool to help understand whether the changes that occurred in the account are cash inflows or outflows, as shown below.

There are four non-current asset accounts: long-term investments, land, buildings, and intangible assets. The land account had no change, as there were no purchases or sales of land. Analyzing the investment account results in the following cash flows: