What causes iron to rust?

In this practical, students put iron nails in various conditions including wet, dry, air-free and salty to find out what causes iron to rust. The experiment will need to be set up in one lesson and then left for more than 3 days before being re-examined. It could be left set up for longer if necessary.

Equipment

Apparatus

- Eye protection

- Test tubes, x4

- Test tube rack

- Rubber bung to fit test tube

- Cotton wool

- Forceps

- Pen or other means of labelling test tubes

Chemicals

- Iron nails, x4

- Anhydrous calcium chloride granules (IRRITANT) (see note 3)

- Cooking oil

- Deionised water

- Boiled deionised water (boiled for 15 minutes – see note 5)

- Sodium chloride (table salt)

Health, safety and technical notes

- Read our standard health and safety guidance.

- Wear eye protection throughout.

- Anhydrous calcium chloride, CaCl2(s), (IRRITANT) – see CLEAPSS Hazcard HC019A. Students with sensitive skin should be offered gloves.

- Sodium chloride, NaCl(s) – see CLEAPSS Hazcard HC047b.

- It is best if the deionised water is boiled, eg in a kettle, as close to the start of the lesson as possible and supplied warm to the students. They could boil it themselves for 15 minutes in a beaker on a Bunsen burner, but whether this is advisable will depend on the class.

Procedure

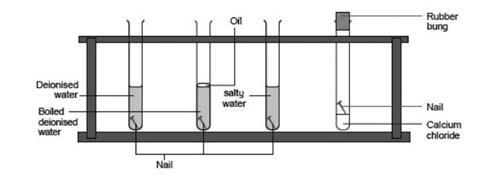

Show Fullscreen

Source: Royal Society of Chemistry

Equipment for investigating the conditions required for rusting to occur

- Label the test tubes 1–4.

- About 1/4 fill tube 1 with deionised water and add a nail.

- About 1/4 fill tube 2 with boiled deionised water and add a nail. Carefully pour a little oil over the surface to prevent air from reaching the water.

- Mix some salt with some deionised water to make a solution. About 1/4 fill tube 3 with this mixture and add a nail.

- Put a nail into tube 4 and add about 2 cm depth of anhydrous calcium chloride granules (these absorb water). Put a bung in this tube to prevent any further water from getting in.

- Leave for at least three days and then note any changes in appearance of the nails.

Teaching notes

You could ask students to tabulate which conditions are present or absent in each of the tubes:

- Tube 1 – water and air

- Tube 2 – water but no air (it is removed during boiling and the oil prevents any extra from dissolving in the water and reaching the nail)

- Tube 3 – water, air and salt

- Tube 4 – air, no water (the calcium chloride removes the water from the air and the bung prevents any extra from entering)

They should see that the nails in tubes 2 and 4 do not rust. The nail in tube 3 rusts the most. From this they should be able to conclude that water and air (actually oxygen in the air) are essential for rusting. Salt can increase the rate of rusting. This can lead to a discussion about rust protection and methods which can be used to keep air and water away from the iron such as paint, grease and plastic coating.

Very simply, rusting is the reaction of iron with oxygen – but water is an important part of the process too.

Additional information

This is a resource from the Practical Chemistry project, developed by the Nuffield Foundation and the Royal Society of Chemistry.

Practical Chemistry activities accompany Practical Physics and Practical Biology.

© Nuffield Foundation and the Royal Society of Chemistry